Open Renewal is a constructive theology that is Jesus-centric, informed by Open Theism’s emphasis on the love of God, and dependent on the Holy Spirit’s renewing work both for personal spirituality and in the implementing of Jesus’ kingdom. Open Renewal brings together insights from historical, recent, and practicing theologians, particularly John Wesley, Clark Pinnock, John Sanders, Thomas Jay Oord, and Greg Boyd.

While they wouldn’t necessarily label themselves open theists, Tom Wright and Brian Zahnd contribute core ideas.

“Open Theism—an Alternative to Classical Theology” | Pasadena Mennonite Church | July 6, 2025

Discussion of Greg Boyd’s Crucifixion of the Warrior God at the SPS session of AAR/SBL in Denver, November 2018.

Videos related to Open Theism

Richard Rice from AAR 2014 in San Diego

John Sanders from AAR 2014 in San Diego

Tom Oord at the Randomness and Foreknowledge conference in Dallas in 2014

Robert Russell at the Randomness and Foreknowledge conference in Dallas in 2014

Richard Swinburne at the Randomness and Foreknowledge conference in Dallas in 2014

William Hasker at the Randomness and Foreknowledge conference in Dallas in 2014

From the Word Made Fresh event at AAR/SBL 2011 on the Life and Legacy of Clark Pinnock

Tom Oord’s lecture "For the Sake of Love… I Embrace Open and Relational Theology" from the 2022 Open and Relational Theology Conference in Wyoming.

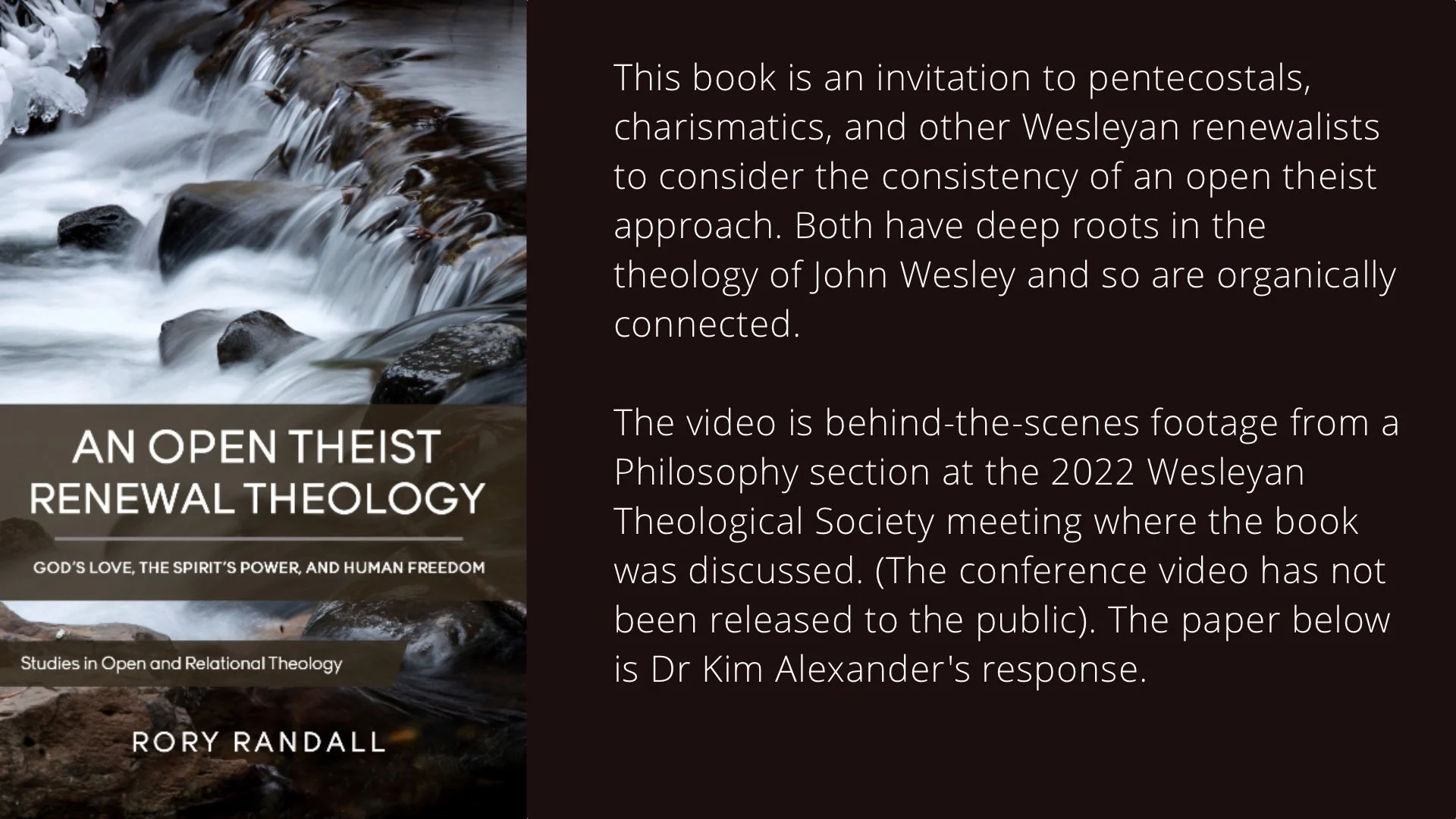

Behind-the-scenes footage from a Philosophy section at the 2022 Wesleyan Theological Society meeting (conference video has limited access).

Videos from SPS 2023

Plenary panel discussion at the 2023 Annual Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies

Presenters: Kimberley Ervin Alexander, Melissa Archer, Mark J. Cartledge

Respondents: Rebecca Basedo-Hill, Asia Lerner-Gay

Chair: Margaret "Peg" English de Alminana

Sisters, Mothers, Daughters: Pentecostal Perspectives on Violence Against Women, eds. Kimberly Ervin Alexander, Melissa L. Archer, Mark J. Cartledge, and Michael D. Palmer (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2022)

Forgiveness as an Element of Healing in the DR Congo

Rory Randall with interviews by Irene Kabidu and survivors at Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, DRC

Intercultural Studies Interest Group at the Society for Pentecostal Studies 2023 Annual Meeting in Tulsa, OK

Three books of interest:

The Crucifixion of the Warrior God: Interpreting the Old Testament’s Violent Portraits of God in Light of the Cross

Greg Boyd (two volumes)

Depictions of God in the Old Testament can be troubling to people who believe God to be wholly loving. Greg Boyd does an amazing job of arguing for a cruciform hermeneutic: just as Jesus humbled himself in the incarnation and crucifixion, Yahweh condescended to interact with the humans he loved in ways they could understand.

Cross Vision is the more condensed version.

Written in 2006, Greg Boyd’s book is prophetic given the rise of Christian Nationalism.

The Openness of God: A Biblical Challenge to the Traditional Understanding of God

Clark Pinnock generated remarkable interest in open theism in the 1990s with the publication of The Openness of God in collaboration with Richard Rice, John Sanders, William Hasker, and David Basinger. This watershed book built on prior technical articles to make the case for open theology (see footnote below).

Richard Rice, in the first chapter of The Openness of God, describes how the open view is consistent with scripture. In the second chapter, John Sanders looks at historical considerations, especially how Greek philosophy has influenced Christian thought. In the third chapter, Clark Pinnock describes how God is responsive, involved in history, and genuinely loving in the open view. William Hasker in the fourth chapter discusses philosophical issues related to open theism. And in the fifth chapter, David Basinger looks at the pastoral implications of openness theology.

The book had significant antecedents: William Hasker, "Foreknowledge and Necessity," Faith and Philosophy 2 Ap 1985. William Lane Craig, The Only Wise God: The Compatibility of Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987). William Hasker, God, Time, and Knowledge, Cornell Studies in the Philosophy of Religion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989). Gregory A. Boyd et al., Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom: the Coherence of Theism: Omniscience, Brill's Studies in Intellectual History 19 (Leiden: New York, 1990). Then, of course, there is the late Jürgen Moltmann's ground-breaking The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology (Der gekreuzigte Gott), 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1974, 1991).